From Africa to Mecklenburg: A Nearly Forgotten Story

During the colonial era, different cultures also intersected in Mecklenburg. Dr. Bernd Kasten, Schwerin’s city archivist, has traced the footsteps of these encounters.

How did German colonialism in Africa impact Mecklenburg? How did African expedition helpers end up in Schwerin or Rostock in the early 20th century? And how did the encounters between these different cultures unfold? These are the questions Schwerin’s city archivist Dr. Bernd Kasten has now explored—with fascinating results.

Africans in Mecklenburg from 1905 to 1925

For a lecture on the topic « Africans in Mecklenburg 1905–1925, » he delved deep into a nearly forgotten history. « This research was more tedious than expected, » Kasten admits. The available sources? Scarce. The possibilities of clarifying open questions? Limited. The motivation? Exceptionally high. After all, images or events whose context isn’t immediately clear don’t let a historian rest.

The Third-Largest European Colonial Power in Africa

As early as the beginning of the 19th century, a few people from Africa—who had ended up there after many adventures—lived in port cities like Rostock. However, general interest in the distant continent was still low at the time. That changed significantly when the German Empire became the third-largest European colonial power in Africa by the late 19th century, behind the United Kingdom and France.

Duke Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg on Expedition

In January 1905, Duke Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg embarked on a months-long journey through East Africa. Since the expedition served not only scientific purposes but also hunting, Carl Knuth, a taxidermist from Schwerin, joined. Hundreds of local porters were recruited to help the caravan move through unfamiliar terrain under scorching heat.

In May 1907, the duke set off again on a cross-continental African expedition. Once more, local helpers were enlisted, including a group of men who had already proven themselves on previous expeditions, many of whom had also participated in 1905. « For the success of this expedition, these 30 men were of outstanding importance—likely far more crucial than the ten white leaders at the front, » says Bernd Kasten.

Local Helpers Unmentioned in Travel Reports

Yet neither their contributions nor their names were mentioned in the travel reports—not even during the third expedition in 1910, when the most important local helpers were even brought to Hamburg beforehand to depart together by ship. « A fundamental justification for the colonization of Africa was the supposed civilizational superiority of Europeans, » the historian explains.

Accordingly, the anthropological studies of the explorers were riddled with prejudices that reinforced the stereotypes of the time. Locals were often regarded as « savages » or portrayed as « dangerous. » This mindset, among other things, justified the corporal punishment of porters—colonialism fueled racism.

Return to Schwerin with Cooks and Servants

The tension between curiosity and condescension also became evident in Mecklenburg when Adolf Friedrich brought a dozen cooks and servants back to Schwerin after his second expedition. Apparently, they were meant to be a striking accompaniment to his triumphant return. Sources speak of the « liveliest interest of Schwerin’s population » upon their arrival at the train station.

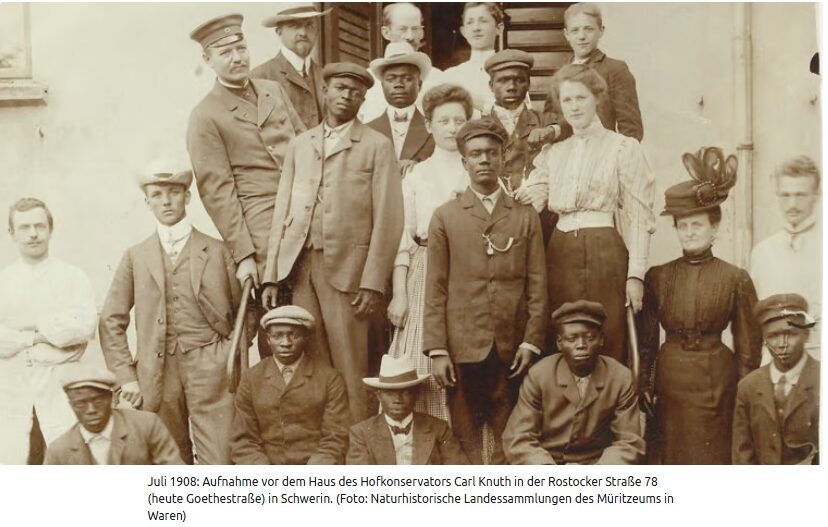

African Visitors in Raben Steinfeld

From this time, there is not only a photograph showing the group visiting court taxidermist Knuth. The twelve men were also taken to Raben Steinfeld near Schwerin, where Adolf Friedrich lived in the castle of his mother, Dowager Grand Duchess Marie. Two hundred members of Schwerin’s military association came to see the African visitors. The Mecklenburgische Zeitung reported on the event in a patronizing tone, expressing surprise that they were « quite well-mannered people. »

Illegitimate Children Left Behind in Togo

After two weeks, the visitors were sent back home. Longer stays were not desired; connections or even equal treatment were unwanted. When Adolf Friedrich—who served as governor of Togo from 1912 to 1914—took an extended home leave in April 1914, local women and illegitimate children remained in Togo. This is documented in several sources Kasten has examined.

World War I and the End of the Colonial Era

Instead, the duke took his cook, 37-year-old Bonifatius Folli, with him. However, due to the outbreak of World War I in the summer of 1914, a return to Togo became impossible, the Schwerin archivist explains. Following Germany’s defeat, the empire had to cede its colonies to the victorious powers—and Folli was stranded in Mecklenburg.

A Cook from Togo Stranded in Mecklenburg

After wartime deployments, the duke lived from 1917 onward in the grand ducal palace at Blücherplatz in Rostock, where his cook also had a room. In 1919, Adolf Friedrich moved to Bad Doberan. Although Bonifatius Folli was allowed to marry the daughter of a merchant who had come from Cameroon to Hamburg, finding housing for himself and his wife in Bad Doberan proved hopeless. Due to the prolonged separation, the marriage eventually ended in divorce, and Folli left Mecklenburg for Berlin, where he became a lecturer in African languages at Berlin University.

The sources are less revealing in the case of Helmut Japende. Apparently, he too had come from Togo to Mecklenburg in 1914 as a horse groom. He may be the only Black man visible in a 1918 photo of workers at the Fokker factory in Schwerin. The only confirmed fact, Kasten says, is that he, like Folli, left Mecklenburg in the 1920s.

A Mix of Fascination, Fear, and Condescension

« The few Africans still living in Germany in the 1930s resided in Berlin and other major cities, » the archivist notes. He would have liked to learn how the visitors experienced their short stays in Mecklenburg—or how Folli fared as Adolf Friedrich’s cook between 1917 and 1923. But as with many historical accounts, only the perspectives of the powerful are available. These, however, provide insight into the German population’s attitude toward the inhabitants of African colonies: a mix, as Kasten summarizes, of « a little fascination, a lot of fear, and a great deal of condescension. »

Lecture on May 7 at the Rostock Cultural History Museum

To hear more of what the head of Schwerin’s city archives has discovered on the topic « Africans in Mecklenburg 1905–1925, » join his lecture on May 7 at 6 p.m. at the Rostock Cultural History Museum. The talk is part of a joint lecture series at the Universities of Greifswald and Rostock on migration and mobility in the region. The background: The Round Table on State History has declared 2025 the thematic year of « Mobility. »

From Africa to Mecklenburg: A Nearly Forgotten Story